[Notes] and "Quotes" for October 2025

By Arnie Berg

Book of the Month

“Why can’t people just get along?”

This question is typically invoked when discussing interpersonal or, less often, community and group relationships. However, this question is seldom directed at international or national relationships. It is precisely this national and international geopolitical scope that R.R. Reno addresses in his book, Return of the Strong Gods.

Reno argues that the instability of the West today is not simply a matter of economics or technology or partisanship but of meaning. In reaction to the violent ideologies of WWII, Western democracies have promoted the “open society”, rejecting strong attachments to nation, faith, and tradition. For decades this ideal seemed to offer peace and prosperity, but it also hollowed out the moral and cultural center of Western life, leaving behind a generation of citizens who no longer feel united by shared purposes.

This is perfectly illustrated by the story of a French woman who grew up in a Parisian suburb that over the years experienced a massive influx of immigrants. During conversations, these residents would often speak excitedly about “going home”, to Syria, Morocco, or North Africa. The French woman’s sense of cultural homelessness was expressed by her fear: “Where will I go to be home?”

According to Return of the Strong Gods, populism and nationalism are not irrational responses but the predictable outcome of people searching for belonging in a world that values open borders, diversity, inclusion, and systems of trade that swap rootedness and independence for economic gain.

What is needed to heal the civic fabric? Reno argues that society needs more than policy tinkering to correct the mistakes of the past. To hold people together we still need to follow “strong gods”, including shared commitments to truth, beauty, and a respect for the sacred dimension of life. The over-reaction to memories of fascism and totalitarianism has caused a drift into meaninglessness, polarization and social fragmentation.

This dilemma often provokes a dangerous turn toward illiberalism, which is effectively a democratic failure taking an authoritarian guise. When a single leader makes the sweeping claim, “Only I can fix it,“ to frustrated and disillusioned citizens, the underlying issue is no longer just ineffective governance, but a crisis regarding the objects of national devotion.

Ultimately, Return of the Strong Gods invites readers to ask not simply how we can “get along,” but what kind of shared loves make genuine community possible, within nations and between them. Only by recovering these deep commitments can the West rediscover both moral clarity and political solidarity.

While Reno laments the breakdown of civic unity, the Apostle Paul reminds us that genuine reconciliation is not political but spiritual. In Ephesians 2 he says:

“For he himself [Jesus] is our peace, who has made the two groups one and has destroyed the barrier, the dividing wall of hostility.”

Jesus Christ offers the model of a unity grounded in love, not political ideology. This model does not erase differences transforms them into a shared spiritual bond.

Find complete details in the book blurb.

Return of the Strong Gods: Nationalism, Populism, and the Future of the West - R.R. Reno (2021)

Runner-up (tie):

Tommy Douglas: The Road to Jerusalem - Thomas H. McLeod, Ian McLeod (1987)

Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future - Dan Wang (2025

“A room without books is like a body without a soul.”

— Marcus Tullius Cicero

Extreme summaries: Frankenstein

Mary Shelley - Monsters are people too.

(from John Atkinson, Abridged Classics)

Quotes of famous last words…

“Don’t worry, I’ve done this a thousand times.“

“Hold my beer and watch this!“

“I drank what?!“

“Who put this violin in my violin case?!“

“Let me show you how to tell if a battery still has charge.“

“I saw this in a YouTube video once.“

“Are you still holding the ladder?“

“I’m sure AI knows what it’s doing.“

“What’s the worst that could happen?“

“Throw me that grenade; I know how to deal with it.“

“It‘s ok, dogs loves me.“

“Oh, they changed the color of my pills.“

List of book blurbs for October 2025

🏛 Among the books addressing Politics, Power, and Society are:

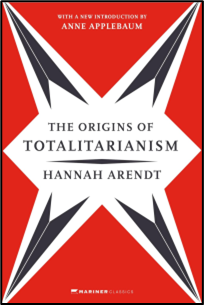

The Origins of Totalitarianism

Hannah Arendt (1951, 576 pp.)

How antisemitism and imperialism birthed modern totalitarianism.

Return of the Strong Gods: Nationalism, Populism, and the Future of the West

R.R. Reno (2021, 208 pp.)

How populism reflects the West’s longing for meaning and solidarity.

Kamela Harris (2025, 321 pp.)

Harris recounts the intensity and lessons of her abbreviated presidential campaign.

Tommy Douglas: The Road to Jerusalem

Thomas H. McLeod, Ian McLeod (1987, 341pp.)

Chronicles the career of the visionary Canadian politician who pioneered universal healthcare.

📖 Faith, Theology, and Meaning

Encountering Jesus in Revelation: The Apocalyptic Perspective That Calls Us to Follow the Lamb

Ben Boeckel (2024, 206 pp.)

Boeckel unveils Revelation’s call to follow the Lamb amid worldly powers.

💔 Human Experience and Reflection

Miriam Toews (2025, 192 pp.)

Toews reflects on loss, creativity, and the lingering ache of family grief.

🌏 Global Change and Technology

Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future

Dan Wang (2025, 288 pp.)

Explores how China’s engineer-driven model is reshaping global innovation, contrasting with North America’s legal/procedural-driven model.

Now, back to reading!

We hope you find something of interest in this month's selections and look forward to your feedback! My goal is simply to share a bit of my reading experience in hopes of sparking interest and awareness among readers. My hope is that as you read through the Notes and Quotes, you won’t just superficially skim the surface of the book, but that you’ll really get a feel for the heart and soul of the book and connect with the author’s deeper message.

My intent is to provide:

Notes on each book I’ve read this month (bracketed by ‘[AB: …]’).

Standout quotes from the book (bracketed in quotes).

No formal ratings or recommendations—just highlights that give a flavor of the book.

Keep scrolling for more ‘Notes and Quotes’ …

The Origins of Totalitarianism

Hannah Arendt (1951, 576 pp.)

Genre: Political theory

[Notes:

Hannah Arendt (1906-1975) published this book at the age of 45. She was a political theorist and academic after earning a Ph.D. in Philosophy at Heidelberg.

I was initially drawn to this book for its analysis of totalitarianism, but I also had a personal curiosity about the historical discourse that was current and documented during the year I was born.

Arendt structures The Origins of Totalitarianism into three distinct sections. She first dedicates significant space to analyzing racism, particularly antisemitism, and then turns to examining the growth of imperialism. Arendt posits that these two nineteenth-century movements laid the ideological and historical foundation for the rise of totalitarianism, which she discusses in the final third of the book, detailing how it developed out of and built upon its precursors in the early twentieth century.

Not only is this a laborious book to read, but it is one of the most depressing books I have read. It left me convinced that what history observed as the scaled-up instance of totalitarianism in Nazism and Soviet Marxism is the logical outcome of a movement with a complete lack of moral foundation and the logical result of a system of governing that has abandoned any moral compass.]

Curated Quotes:

“Expansion is everything,’ said Cecil Rhodes, and fell into despair, for every night he saw overhead ‘these stars … these vast worlds which we can never reach. I would annex the planets if I could.’ He had discovered the moving principle of the new, the imperialist era (within less than two decades, British colonial possessions increased by 4½ million square miles and 66 million inhabitants, the French nation gained 3½ million square miles and 26 million people, the Germans won a new empire of a million square miles and 13 million natives, and Belgium through her king acquired 900,000 square miles with 8½ million population); and yet in a flash of wisdom Rhodes recognized at the same moment its inherent insanity and its contradiction to the human condition. Naturally, neither insight nor sadness changed his policies. He had no use for the flashes of wisdom that led him so far beyond the normal capacities of an ambitious businessman with a marked tendency toward megalomania.”

“Only the unlimited accumulation of power could bring about the unlimited accumulation of capital.”“But even slavery, though actually established on a strict racial basis, did not make the slave-holding peoples race-conscious before the nineteenth century. Throughout the eighteenth century, American slave-holders themselves considered it a temporary institution and wanted to abolish it gradually. Most of them probably would have said with Jefferson: ‘I tremble when I think that God is just.’”

“Colonization took place in America and Australia, the two continents that, without a culture and a history of their own, had fallen into the hands of Europeans.” [AB: This seems to be a very presumptuous claim since each of these continents was already home to an indigenous population with its own long, rich history and unique culture. In hindsight, however, this was likely a prevailing Eurocentric attitude during the period Arendt was writing.]“Now they made apparent what no other organ of public opinion had ever been able to show, namely, that democratic government had rested as much on the silent approbation and tolerance of the indifferent and inarticulate sections of the people as on the articulate and visible institutions and organizations of the country. Thus when the totalitarian movements invaded Parliament with their contempt for parliamentary government, they merely appeared inconsistent: actually, they succeeded in convincing the people at large that parliamentary majorities were spurious and did not necessarily correspond to the realities of the country, thereby undermining the self-respect and the confidence of governments which also believed in majority rule rather than in their constitutions.” [AB: Shades of January 6?]

“To this aversion of the intellectual elite for official historiography, to its conviction that history, which was a forgery anyway, might as well be the playground of crackpots, must be added the terrible, demoralizing fascination in the possibility that gigantic lies and monstrous falsehoods can eventually be established as unquestioned facts, that man may be free to change his own past at will, and that the difference between truth and falsehood may cease to be objective and become a mere matter of power and cleverness, of pressure and infinite repetition.”“The chief disability of totalitarian propaganda is that it cannot fulfill this longing of the masses for a completely consistent, comprehensible, and predictable world without seriously conflicting with common sense. If, for instance, all the ‘confessions’ of political opponents in the Soviet Union are phrased in the same language and admit the same motives, the consistency-hungry masses will accept the fiction as supreme proof of their truthfulness; whereas common sense tells us that it is precisely their consistency which is out of this world and proves that they are a fabrication. Figuratively speaking, it is as though the masses demand a constant repetition of the miracle of the Septuagint, when, according to ancient legend, seventy isolated translators produced an identical Greek version of the Old Testament. Common sense can accept this tale only as a legend or a miracle; yet it could also be adduced as proof of the absolute faithfulness of every single word in the translated text.”

“In the language of the Nazis, the never-resting, dynamic ‘will of the Fuehrer’ – and not his orders, a phrase that might imply a fixed and circumscribed authority – becomes the ‘supreme law’ in a totalitarian state.”“The complete absence of successful or unsuccessful palace revolutions is one of the most remarkable characteristics of totalitarian dictatorships. (With one exception no dissatisfied Nazis took part in the military conspiracy against Hitler of July, 1944.)”

“The famous ‘Right is what is good for the German people’ was meant only for mass propaganda; Nazis were told that ‘Right is what is good for the movement,’ and these two interests did by no means always coincide. The Nazis did not think that the Germans were a master race, to whom the world belonged, but that they should be led by a master race, as should all other nations, and that this race was only on the point of being born.”“Evidence that totalitarian governments aspire to conquer the globe and bring all countries on earth under their domination can be found repeatedly in Nazi and Bolshevik literature.”

“The change in the concept of crime and criminals determines the new and terrible methods of the totalitarian secret police. Criminals are punished, undesirables disappear from the face of the earth; the only trace which they leave behind is the memory of those who knew and loved them, and one of the most difficult tasks of the secret police is to make sure that even such traces will disappear together with the condemned man.”“The one thing that cannot be reproduced is what made the traditional conceptions of Hell tolerable to man: the Last Judgment, the idea of an absolute standard of justice combined with the infinite possibility of grace. For in the human estimation there is no crime and no sin commensurable with the everlasting torments of Hell. Hence the discomfiture of common sense, which asks: What crime must these people have committed in order to suffer so inhumanly? Hence also the absolute innocence of the victims: no man ever deserved this. Hence finally the grotesque haphazardness with which concentration-camp victims were chosen in the perfected terror state: such ‘punishment’ can, with equal justice and injustice, be inflicted on anyone.

In comparison with the insane end-result – concentration-camp society – the process by which men are prepared for this end, and the methods by which individuals are adapted to these conditions, are transparent and logical. The insane mass manufacture of corpses is preceded by the historically and politically intelligible preparation of living corpses. The impetus and what is more important, the silent consent to such unprecedented conditions are the products of those events which in a period of political disintegration suddenly and unexpectedly made hundreds of thousands of human beings homeless, stateless, outlawed and unwanted, while millions of human beings were made economically superfluous and socially burdensome by unemployment. This in turn could only happen because the Rights of Man, which had never been philosophically established but merely formulated, which had never been politically secured but merely proclaimed, have, in their traditional form, lost all validity.”Return of the Strong Gods: Nationalism, Populism, and the Future of the West

R. R. Reno (2021, 208 pp.)

Genre: Political Commentary

[Notes:

At first, I had some misgivings about this book as I had heard it described as ideological fuel for some of the “intellectuals” orbiting the MAGA movement.

R.R. Reno, an American Catholic theologian, political philosopher, and currently editor of First Things magazine, writes from a tradition that aims to “advance a religiously informed public philosophy for the ordering of society.” As Ross Douthat once noted, First Things showed that “it was possible to be an intellectually fulfilled Christian.”

R. R. Reno earned a Ph.D. in Religious Studies from Yale and taught theology at Creighton University for twenty years.

In Return of the Strong Gods, Reno traces how the trauma of two world wars (1914–1945) instilled a deep desire in both the political left and right to prevent the rise of fascism. Fascism had been animated by “strong gods,” as he calls them, “the objects of men’s love and devotion—the sources of the passions and loyalties that unite societies.” In place of these, the West embraced the “post-war consensus” of the “open society,” favoring tolerance, multiculturalism, and pluralism over solidarity. The result, Reno argues, has been a spiritual and cultural vacuum, one that contemporary nationalism now seeks to fill with renewed meaning, belonging, and solidarity. In some ways, this book acts as an antidote to the despair of The Origins of Totalitarianism.

On balance, this book appeals equally to the politically right and the left.]

Curated Quotes:

“Arthur Schlesinger Jr., a bestselling historian and establishment intellectual who did much to form governing opinion after World War II, outlined an American response to totalitarianism in his book The Vital Center: The Politics of Freedom (1949). Capitalism and technology, he argued, release modern man from his traditional social bonds, leaving him homeless and atomized—a condition similar to Popper’s “strain” of freedom.”

“The cultural scene is very different in the twenty-first century. Few recent college graduates can name a living poet. We now turn to social psychology, brain science, evolutionary theory, and economics to understand our lives and our society. Science provides the tools to diagnose problems and formulate solutions, much as Popper had hoped. Devoid of transcendence, these ways of thinking are materialist, not in the moral sense of encouraging greed and consumption (though some do that too) but in the metaphysical sense of reducing human reality to instincts and biological processes. Why read Jane Austen when it’s obvious that economic theory provides a more objective and reliable guide to the dating and marriage marketplace?” [AB: Secular education with a deficiency in the humanities.]“Camus presents a narrative argument: We can resist totalitarian evil only if we seek solidarity in the ordinary realities of life. He preached a humanism of little worlds, an outlook that renounces the lure of transcendence that tempts us to try to live up to seemingly noble principles and grand ideals. Our ambition should be to honor ordinary life, not to sanctify or otherwise ennoble it. “ [AB: Rising authoritarianism and totalitarianism is a recurring theme.]

“The West won the Cold War in 1989. This is not something Burnham expected, though I’m sure he would have been thrilled, as all of us were, when the Berlin Wall fell. Little did we know that the West’s release from that life-and-death struggle would expose it to the full force of the postwar consensus and its hostility to the strong gods. Unrestrained by the existential threat of communism, the Western postwar consensus tended toward pure negation, leaving us a utopian dream of politics without transcendence, peace without unity, and justice without virtue.”“The educational culture of the West manifests a pattern of weakening. We no longer think of higher education as the source of strong truths. It is instead devoted to critique and reduction. An educated person in the twenty-first-century West is an expert at unmasking pretentions to transcendent truth, exposing them as instruments of economic competition, class domination, patriarchy, and white privilege, or as products of the blind struggle of our genes to survive.” [AB: This kind of education was desired at the end of the Cold War as it was expected to reduce the likelihood of totalitarianism and authoritarianism as described in The Origin of Totalitarianism.]

“Most of the liberals of his [James Burnham, from Suicide of the West: An Essay on the Meaning and Destiny of Liberalism, 1964] day were anti-anticommunists. They ardently opposed anything “strong,” even strong denunciations of communism, which they too rejected, worrying that in anything strong lay the seeds of an authoritarian personality. In the place of traditional loyalties to “God, king, honor, country” and “a sense of absolute duty or an exalted vision of the meaning of history,” liberalism “proposes a set of pale and bloodless abstractions.”“[James] Burnham was an American conservative, which means he was concerned to defend the American liberal tradition, broadly understood. In the early 1960s, however, he articulated the important insight that no culture survives without strong gods. This is as true for an open society as a traditional one. A society lives on answers, not merely questions; convictions, not simply opinions. The political and cultural crisis of the West today is the result of our refusal—perhaps incapacity—to honor the strong gods that stiffen the spine and inspire loyalty. We are subjected to the increasingly shrill insistence that “critical questioning” is the highest good and “diversity is our strength.”

“But we are not living in 1945. Our societies are not threatened by paramilitary organizations devoted to powerful ideologies. We do not face a totalitarian adversary with world-conquering ambitions. Insofar as there are totalitarian temptations in the West, they arise from the embattled postwar consensus, which is becoming increasingly punitive in the face of political populism and its rebellion against the dogmas of openness. Our problems are the opposite of those faced by the men who went to war to defeat Hitler. We are imperiled by a spiritual vacuum and the apathy it brings. The political culture of the West has become politically inert, winnowed down to technocratic management of private utilities and personal freedoms. Our danger is a dissolving society, not a closed one; the therapeutic personality, not the authoritarian one.” [AB: How long can a “feel-good” yet lonely society last?]“One conversation stands out. A younger friend, agonizing over the choices he faced in life, asked for advice. I told him I couldn’t help very much. For me, life has been like a train ride. The engine of strong cultural norms pulled me through life’s stages: college, job, marriage, children. In its time, the train will take me to retirement and, of course, death. He replied, “No, no—life’s not like that anymore. Now it’s a sailboat that you pilot first this way and then that in order to make your way to the destination of your own choosing.” It struck me as an exhausting way to live.”

“Economic globalization, diversity ideology, and mass immigration enjoy the prestige of weakening and lightening. These powerful cultural imperatives explain why today’s populism generates such anxiety among our leadership class, even to the point of hysterical worries about the return of the 1930s. Populism is more than a rebellion against outsourcing, political correctness, and too many foreigners. It is a rejection of the postwar consensus. This frightens our leadership class, for it has been socialized into the ahistorical conviction that the imperatives of the open society are the only legitimate basis for economic and political arrangements. All other alternatives, our establishment believes, lead back to fascism. They are roads to serfdom.”“What’s less controversial is the stark fact of middle-class economic stagnation in the West. Specialists argue about the data. Some say that when one factors in lower costs for consumer goods and government transfer payments the stagnation is not so evident. Nevertheless, I will venture a broad judgment of our present circumstances: The erosion of the prosperity of the middle class in the West has undermined political solidarity. The prospects for moderately educated, middle-of-America workers have declined over the last generation, while globalization has worked out nicely for the well-educated, largely coastal elites. The specifics vary in other countries in the West, but the basic pattern is similar. The rich have a role in the global system; the middle class is increasingly homeless.” [AB: When the middle class loses economic growth while the wealthy thrive, inequality ceases to be just an economic issue. It fractures the social fabric and erodes hope in the common good.]

“In an analysis in 2012 of the shift in technology manufacturing from the United States to China, reporters for the New York Times found that nearly all of Apple’s products were manufactured abroad. “It isn’t just that workers are cheaper abroad,” the journalist noted. “Rather, Apple’s executives believe the vast scale of overseas factories as well as the flexibility, diligence and industrial skills of foreign workers so outpaced their American counterparts that ‘Made in America’ is no longer a viable option for most Apple products.” [AB: For more details on this shift, see Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future.]“Well-to-do Americans have handled fifty years of openness reasonably well, but cultural deregulation has been hell on the bottom 30 percent. Many people took issue with Donald Trump’s dark inaugural address in January 2017, with its talk of “carnage.” “Aren’t things pretty good?” they asked. That response is evidence for Murray’s thesis that over the past two generations there has been a pronounced divergence in quality of life between the open society’s winners and losers. The upper portion of society has an economic and cultural home in the system; those at the bottom do not. Meanwhile, denizens of the vulnerable middle class are anxious that they, too, will be homeless, sidelined in the global economy and lumped among the “uncreative” and close-minded. The upper end of society is sheltered; the rest are not.” [AB: The ironic appeal of trump, the attraction of a self-professed “winner” to anxious “losers”.]

“Our situation today is not a happy one. Cultural deregulation was always implicit in the early postwar campaign against the “authoritarian personality” and in the shift from truth to meaning. It has become explicit in diversity therapies and multicultural rhetoric. The open society can tolerate no strong cultural norms, for they define the domain of the “normal.”“In the open culture, the lives of ordinary people become more disordered and less functional. Civic solidarity is undermined and fears about discrimination fester. When racial tensions increased during Obama’s eight years as president, commentators assumed the cause was white backlash. This is always the pattern of the postwar consensus: social problems stem from closed-society vices. Our leadership class is unable to countenance the obvious explanation: They are dysfunctions of an open society.”

“After Britain’s vote to leave the European Union, countless commentators fell unselfconsciously into derogating those who voted for “Brexit” as rustics, rubes, and racists while implicitly complimenting themselves as cosmopolitan and inclusive. Something similar has been at work in the United States for some time. You can “have” diversity even if you live in a gated community simply by mouthing the pieties of the open culture. Those who don’t are, as Hillary Clinton notoriously put it, “deplorables.”“Of course, in the early decades of the postwar era, the proponents of an open society could take its underlying solidarity for granted. The Cold War kept the West tensed with collective purpose. But the demise of the Soviet Union removed limits to utopian ideals of openness, which now bear upon us with dissolving urgency.” [AB: Assumed solidarity.]

“When talking to a smart graduate student in Cambridge, Massachusetts, doing work in social policy, I was not surprised to discover that he could not formulate a reason to give preference to an unemployed worker in Ohio over someone in Senegal who wants to migrate to the United States. More and more voters in the West sense this strange inability among our leadership class to affirm their loyalty to the people they lead. And so voters suspect, correctly, that those who lead are not willing to protect them from economic competition or cultural displacement. Their leaders will not do what leaders are supposed to do, which is to protect and preserve the realm, to sustain and build up our shared home.” [AB: “Save our home.”]“Today’s populism rejects the deregulatory “openness” consensus. One of Trump’s most striking campaign promises was to build a “beautiful wall” on our southern border, a symbol of closure, not openness. Trump attacked other aspects of the bipartisan establishment as well, promising to rip up free-trade agreements and to protect American industries. He repeatedly, pungently, and unapologetically violated the canons of political correctness, the police arm of cultural openness. And his entire campaign was based on an unnuanced, pro-American slogan: “Make America Great Again.” [AB: Under this philosophy, restrictive tariffs and an “America First” policy make sense.]

These signature stances sin against the postwar consensus. During the campaign, mainstream conservatives howled with indignation about the threat Trump posed to free-market principles. Foreign policy experts warned that he would torpedo the “rules-based international order.” Liberals were outraged that Trump’s (to them) obvious demonstrations of sexism, racism, and general hostility to every principle of an open and inclusive society failed to derail his candidacy. What’s wrong with American voters?” [AB: A question we have often asked ourselves!]“Trump’s message to voters was not “I will open things up to create opportunity and economic growth.” It was “I will defend you.” His message was not “Diversity is our strength.” It was “America is for Americans.” His message was not “Our job is to lead the world.” It was “My job is to look out for our country’s interests.”

Think what you want of Trump, ill or well, but think clearly. He contradicts the postwar governing consensus, as do many populist political figures in Europe. He is the anti–George H. W. Bush: strong borders, not open ones; advantageous trade, not open trade; loyalty and patriotism, not open minds.” [AB: i.e., “strong” gods, not “open society”.]

“All flesh is like grass. Donald Trump will pass from the scene, as will the other politicians now in the news. But they foretell change, not just in what they say but in the often exaggerated, anxious, and hysterical responses they evoke from a failing establishment in the West. The rising tide of populism suggests a rejection of the postwar consensus. The winds are shifting. More and more people in the West want the strong gods to return.”“The death of old gods in no way means the death of the sacred. We are social animals, and public life requires the aroma of the sacred. Durkheim admitted that he could not foresee what form the new gods would take, but he was right about the general trend. He died in 1917, living only long enough to see the first intimations of the gods who would storm through Europe with fire and steel.”

“It was widely believed that the cultural calamity of 1914–1945 required paradoxically strong medicine to weaken the power of the sacred to build loyalty and solidarity. This was an understandable response. Men do horrible things in the service of strong gods. Traditional societies justify radical inequalities, calling them expressions of sacred hierarchies. They demand terrible sacrifices for collective aims perfumed with transcendent claims. Modern societies have inflicted unspeakable brutalities in the service of utopian ideologies that claim the supreme sanction of History. Would it not be better to live without the strong gods, old or new? Isn’t skeptical doubt safer than faith and devotion? Isn’t a thoroughgoing and permanent critical disposition for the best? Aren’t we better off with an anti-dogmatic spirit? If we must have gods, shouldn’t they be weak, not strong: difference, dialogue, diversity, and other motifs of openness, or efficiency, productivity, and utility, the bloodless, technocratic metrics that leave us unmolested in our “little worlds”? [AB: In other words, based on “DEI” (Diversity, Equality, and Inclusion), which in itself is desirable.]“In his massive account of world history, The City of God, Augustine defines the “we” as “an assembled multitude of rational creatures bound together by a common agreement as to the objects of their love.”

“The postwar consensus critiques, deconstructs, and deflates a great deal of what the Western tradition has championed as fitting objects of our love—not only God, but the nation and our cultural inheritance, even truth itself. By certain measures, the postwar consensus has been remarkably successful. It has brought calm to the West and great wealth as well.”“Public life, domestic life, and religious life: these are what Russell Hittinger has called the three “necessary societies.” The strong gods are returning in the public realm, animating the populism that seeks to restore the nation. If we are to encourage this restoration of solidarity with intelligence, we must pursue a wider strategy of strengthening. Throughout the history of the West, communities of transcendence have pinioned the nation from above, while the marital and domestic bonds of family loyalty have pinioned it from below. Let us learn from this history: The best safeguards against the dangers of love’s perversion are the loves that ennoble and give us rest. The solidarities of domestic life and religious community are not at odds with the civic “we.” On the contrary, the strong gods can reinforce each other, preparing our hearts for love’s many devotions. A man who makes sacrifices for his family or for his faith is likely to be ready to give the full measure of devotion to his country.”

“I am increasingly convinced that our political upheavals reflect a crisis of the postwar consensus, which socializes us to regard our highest duty as preventing the return of the strong gods and the gifts of solidarity they bring. To insist upon the weakening and disenchantment that banished the strong gods from the postwar West is profoundly wrongheaded and will bring woe, not peace. For deprived of true and ennobling loves, of which the patriotic ardor is surely one, people will turn to demagogues and charlatans who offer them false and debasing loves.

Our task, therefore, is to restore public life in the West by developing a language of love and a vision of the “we” that befits our dignity and appeals to our reason as well as to our hearts. We must attend to the strong gods who come from above and animate the best of our traditions. Only that kind of leadership will forestall the return of the dark gods who rise up from below.” [AB: I hear in this a call to the “strong gods” of transcendence, faith, and commitment, paired with a genuine respect for the kind of diversity, equality, and inclusiveness embodied in the teachings of Jesus Christ.]107 Days

Kamela Harris (2025, 320 pp.)

Genre: Political memoir

[Notes:

Kamala Harris wrote this memoir in 2025 at the age of 61. Prior to the election she served as U.S. Vice-President (2021-2025) and before that as U.S. Senator and California Attorney General.

This may be unfair, but while I was looking for some insightful analysis and thoughtful diagnosis, this book read more like a daily journal, dwelling on feelings and relationships rather than substance. Instead of parsing why Harris lost the election, she seems to be preoccupied with finding someone, or something, to blame.]

Curated Quotes:

“Polling revealed that many of these young voters didn’t feel they knew me. And contrary to some predictions, they did not vote primarily on reproductive rights, or Gaza, or climate change. They voted on their perceived economic interests. In a postelection study conducted by Tufts University, 40 percent put the economy and jobs as their top issue. (The next priority was abortion, 13 percent. Climate change was a top issue for 8 percent; foreign policy, including Gaza, 4 percent.)

My policies, which would have helped young voters with protection for renters, a home down payment, or student debt relief, or elevating the opportunities of non–college graduates, or increasing access to capital, had not cut through the false notion that Trump was some kind of economic savant who would somehow be better for their personal financial position.

In 107 days, I didn’t have enough time to show how much more I would do to help them than he ever would. And that makes me immensely sad.”

“Anderson Cooper would make news out of the CNN town hall. He did it with the first question. “You’ve quoted General Milley calling Donald Trump a fascist. You yourself have not used that word to describe him. Let me ask you tonight, do you think Donald Trump is a fascist?”

“Yes, I do. Yes, I do. And I also believe that the people who know him best on this subject should be trusted.”

That became the headline. I was trying to make sure that the audience knew that John Kelly, Trump’s former chief of staff, had said he thought the former president met the definition of the word and that Trump had often praised Hitler. I wanted voters to know that the men closest to him, members of his own administration, thought he was a fascist.

The stronger answer would have been: Never mind what I think, listen to what his generals and top officials say. To have your own people who have worked with you say such a thing is far more damning than the opinion of your political opponent.” [AB: Shoulda coulda woulda.]“What had been a big problem for the Trump campaign had been turned, instead, into a mess for us.” [AB: After Biden’s gaffe of putting on a MAGA hat at a union rally.]

“My team, desperately seeking privacy [after receiving reports of having lost the election], decamped to Lorraine’s car. Crammed into the small Audi hybrid, they took another call from JOD. Then JOD called me. “I’m sorry, ma’am. I don’t think you’re going to get there.”

“Oh my God. What’s going to happen to our country?”

I could barely breathe.

“Should we fight this?”

“We’re just not in the zone to ask.”

I walked down the stairs in shock. Chrisette and Meena were the first people I saw, sitting together on the couch. I looked at them, slowly shook my head.

They had been with me in every campaign, and we had never experienced a loss.

They both started to cry. Nik, sensing the tension, gathered up Amara and Leela and took them to their bedroom.

All I could do was repeat, over and over, “My God, my God, what will happen to our country?”“The authoritarian, nationalist Project 2025 is the blueprint for the Trump administration’s second term. As of this writing, of its 316 objectives, 114 have been fully realized and 64 more are already in progress.

The Justice Department is going after Trump’s enemies list, while Trump supporters have been pardoned and released: January 6 rioters who attacked police, the fentanyl dealer Ross Ulbricht, numerous tax cheats.

Foreign leaders have played him with flattery, grift, and favor. A luxury jet, or a Trojan horse?

He has lined his own pockets and enriched billionaires while doing nothing for the middle class and worsening the condition of the poor.

The destruction of scientific research aimed at fighting our worst diseases and the climate crisis, the targeting of SNAP, Medicaid, and programs for our veterans, the deterioration of our global friendships, the terrorizing of our immigrant communities, the starvation and sickening of millions around the world for lack of foreign aid, the reckless abandonment of clean energy, the rollback of environmental protections, the attack on intellectual freedom in our universities, the bullying of law firms, the breathtaking corruption. I could go on.

Trump says he has a mandate for these things. He does not.

His victory was whisker-thin. He beat me by 1.5 percentage points in one of the closest elections in a century. A third of the electorate voted for me. But a third of the electorate stayed home. That means two-thirds of our country did not elect Donald Trump.

Two-thirds of us did not choose this man or his agenda.

That’s why I have no patience for anyone saying, I’m giving up on America because America wanted this. We did not. Of the third that voted for Trump, a good part of them voted for him on promises unkept.

He did not “immediately bring prices down starting day one.” Instead, the opposite. He did not “cut energy prices in half within twelve months.” He could not bring peace to Ukraine “before I even become president.” Instead, he has acted as enabler to the aggressor and shamefully attacked a brave leader defending democracy.

I predicted all that. I warned of it. What I did not predict: the capitulation.

The billionaires lining up to grovel. The big media companies, the universities, and so many major law firms, all bending to blackmail and outrageous demands.”

“What we the people must understand is that the dismantling of our democracy did not start with the 2024 election.

The right-wing and religious nationalists have played the long game, working for decades to take over state houses, gerrymander districts, and dominate local government boards. Their think tanks like the Federalist Society created the blueprint for stacking the Supreme Court, while the Heritage Foundation created Project 2025.

Their plans have been amplified by the rise of a right-wing media ecosystem built to operationalize their agenda through massive propaganda, misinformation, and disinformation. Trump was their vehicle, his road paved for him, years earlier, by a hot and pungent brew: Ronald Reagan’s celebrity, Newt Gingrich’s belligerent discourse, and Pat Buchanan’s nativism.

Don’t be duped into thinking it’s all chaos. It may feel like chaos, but what we are witnessing is a high-velocity event, the swift implementation of an agenda that was written many decades ago.”Tommy Douglas: The Road to Jerusalem

Thomas H. McLeod, Ian McLeod (1987, 341 pp.)

Genre: Political biography

[Notes:

Thomas H. McLeod, who passed away on January 1, 2008, was 69 years old when he co-authored this book. He held a Ph.D. in Economics from Harvard University and served in the Saskatchewan government before transitioning to academia. In 1952, he became Dean of the College of Commerce at the University of Saskatchewan, and later served as Vice-Principal and Dean of Arts and Science at its Regina campus.

His son, Ian McLeod, collaborated with him on the book while pursuing a career in journalism in Calgary.

My good friend Marshall was well acquainted with both of these gentlemen.

As a native Saskatchewanian, I found much that is relatable in this book. The legacy of Tommy Douglas continues to shape the mindset and politics of Saskatchewan to this day.

Douglas did graduate from a Baptist university college which later became Brandon university

Several surprises emerged from this book. During his academic career at the Baptist university college in Brandon, Tommy Douglas was an ardent student of eugenics, a widely accepted subject in those days, though the movement quickly lost credibility as its scientific limits and moral failings set in. This college, operating under the Baptist General Conference, later became the Brandon University after the BGC withdrew their support.

What struck me the most, however, was the extent of communist influence across the Prairie provinces during the 1930s as people were grasping at whatever ideology worked to overcome the hardships of the Great Depression. Although Douglas flirted with working with the communists, their professed commitment to preserve democracy proved empty after the Soviet Union signed a peace pact with Germany in 1939, weakening their influence. Equally surprising was the fact that the Ku Klux Klan made significant inroads in Saskatchewan during those “dirty thirties.”

Tommy Douglas worked to establish a socialist welfare state with uncompromising respect of the individual liberties and free enterprise.

The reference to “Jerusalem” in the title alludes to the “The New Jerusalem” of the Book of Revelation. Douglas’s thinking, typical of mainstream Protestantism, reflects the belief that with enough moral conviction and political will, the Kingdom of God could be realized on earth.]

Curated Quotes:

“The new pastor [Tommy Douglas] plunged into his work with energy and compassion, determined to do something for the poor of the town. He was gifted with an evangelist’s love of the language and a reformer’s zeal, and he was bright, attractive, and persuasive. But the human suffering grew around him much faster than his confidence in himself. He made common cause with his fellow ministers, and then with a broad group of working people. They needed a leader. They chose Tommy Douglas. Before long he was part of a national reform movement with strong roots in the gospels of Jesus; its key principle was that the economic and social system must be reorganized to serve human need rather than human greed.”

“The social gospel rallied to the idea of progress and the belief that social reform fit in with God’s plan for the evolution of the human species. At its logical extreme, this gospel could be extended to include the “science” of eugenics — as a graduate student Douglas wrote his Master’s thesis on the possibilities for developing a healthier human race by regulating marriage and sterilizing the unfit. More typically, the social gospel put forward a generalized optimism, teaching that God was leading an ever-improving mankind onward and upward to the New Day.”“Douglas’s flirtation with eugenics was not simply an effort to please a professor. He returned to the same theme in 1934, in an article published in the Saskatchewan CCF Research Review under the heading “Youth and the New Age.” He wrote: “The Kingdom of God is in our midst if we have the vision to build it. The rising generation will tend to build a heaven on earth rather than to live in misery in the hope of gaining some uncertain reward in the dim, distant future.” The church, he said, must take an active part in social change if it is to uphold the law of God. As an example of social change, he praised the “science of eugenics” with its plan to control breeding among “subnormal” families. Future generations would cast superstition aside, he said, and prevent the mentally or physically unsound from rearing families.”

“Besides its economic record, Anderson’s government was also haunted by the circumstances of its birth. It had come to power in 1929 on a wave of reaction—anti-Semitic, anti-immigrant, anti-French, and anti-Catholic— and with the backing of the Ku Klux Klan, which had signed up thousands of members in Saskatchewan. Although the Klan claimed to have no political preferences, observers including Coldwell [associate of Douglas] reported that Anderson had close ties to the extremist group. Gardiner, in contrast, had campaigned against the Klan. Many Catholics and immigrants remained suspicious of the Tories, and regarded Gardiner and the Liberals as the defenders of their rights.”“Douglas was among the greatest political campaigners Canada has known. He showed great ability as an MP and premier, but the election campaign stimulated him beyond anything else. Though he might be worn and weary from the day-to-day demands of his office, the calling of an election worked an amazing transformation. As the fire-horse of the earlier days responded to the station bell, Douglas would burst from the stall, eyes glistening with anticipation, eager to race the distance and join in the excitement.”

“Important as the speech might be in winning a following, however, the meeting really began when the speeches were over. For as long as time would allow, Douglas would remain near the stage, surrounded by people anxious to shake his hand and give their advice or tell him their troubles. It was now that he established the bond between himself and his followers. He had a remarkable ability to concentrate his attention on whoever stood before him. As long as the conversation lasted, that person was the only person in his world. He had a great memory for names and for family ties and family affairs, and this knowledge came readily into play on a second meeting. Anyone meeting Douglas for the first time thought they had made a friend; on meeting him for the second time they were sure of it. As an opposition politician commented, “Douglas doesn’t need to kiss babies, babies kiss him.’’“His [Douglas’] time as public health minister also provided him with one of his classic after-dinner stories. As he told it on countless occasions, he was visiting the mental hospital in Weyburn when he met a patient walking around the grounds. The patient asked him who he was, and Douglas replied, “I’m the premier of Saskatchewan.’’ The patient responded, “That’s all right, you’ll get over it. I thought I was Napoleon when I came here.”

“As premier, Douglas was the unquestioned leader in cabinet, in caucus, and party on matters of policy. He was the government’s practical dreamer. The essence of his leadership, the source of his power over others, was his ability to dream and to cast his dreams in practical forms, to reduce his ideas to precise language, and to articulate them in such a way as to inspire those around him. He also had the ability to explore the ideas of others with an open mind, to analyse and to learn—and, at times, to act as a prodigious critic.““Fundamental changes in the machinery of government brought changes in the role of the premier, changes that, for the most part, were highly compatible with Douglas’s style of leadership. He sought to lead rather than to direct, and he preferred holding joint deliberations to giving orders. His method was essentially Socratic. He deferred to the specialized knowledge of the experts, and did not pretend to have all the answers. He did, however, have a gift for asking the right questions. He also had a remarkable ability to relate expert advice to the facts of real life, and to the real needs of his constituents. Shoyama, a brilliant economist who sat at the centre of many conferences, spoke almost in awe of the premier’s ability to direct the flow of a technical discussion, and, by questioning, keep the experts’ feet on the ground.

In working with his professional staff, Douglas tried to instill a sense of the music of the English language. Johnson and Shoyama once laboured to put together a speech for the premier, only to have him throw it aside with some irritation. Pacing up and down, Douglas dictated a new version with only minutes to go before he had to deliver it. He said later of the first version, “There was no rhythm in it.”

Few things roused Douglas’s ire faster than an attempt to cover uncertainty with a blanket of words. Sooner or later, most of those who worked for him got the lecture on verbal obfuscation. The premier wanted direct reports delivered in sparse, understandable language.

Douglas once highlighted his dislike of bureaucratese by pulling an item from his morning mail. He had his secretary bring in a letter from a voter who was angry about the Saskatchewan Power Corporation’s method of putting up its power lines. Between the signature and the salutation there was one sentence: “Some bugger bust my fence.” “There it is,” said Douglas. “Subject, ‘bugger,’ verb, ‘bust,’ object, ‘fence.’ Why can’t you fellows write like that?”“If Canada could discover a sense of national purpose, many things were possible: public health insurance, a public pension plan, education for all, a redirection of effort towards international development, a new effort to bring about world peace. He closed with the verse that had become a hymn for the British Labour Party:

I shall not cease from mental strife,

Nor shall my sword sleep in my hand,

Till we have built Jerusalem

In this green and pleasant land.”

[AB: From Douglas’ victory speech after winning the national party leadership.]

“As a college student, Tommy Douglas learned to respect the vitality of American politics and culture. The writings of American theologians such as Walter Rauschenbusch and Harry Emerson Fosdick broadened his understanding of the social gospel. He absorbed the optimism of American social science while studying at the University of Chicago. He made Franklin D. Roosevelt, the architect of the New Deal, one of his political role models.”“Douglas belonged to a generation of North Americans who had held out great hopes for the United States as a bulwark of democracy in the postwar world. He had praised the Americans for their role in setting up the United Nations, and he was strongly pro-Zionist. NATO, he had believed in the late 1940s, would function as a bloc within the United Nations, an economic and military alliance of liberal states, and could lead the way in helping developing nations. By the mid-1950s, he had grown disillusioned with the neighbouring superpower; the United States, he told M. J. Coldwell, had “allied itself with dictatorships and every form of reaction.” The hopes for economic co-operation within NATO were fading as the Americans carried out a “mad rush to build up military might.” [AB: The seeds of dysfunction were sown early in the United States. This may be an example of the principle that you reap what you sow.]

“Douglas’s views on the place of Quebec under a new constitution were, to some extent, a puzzle in shifts and contradictions. His commitment to a constitutional Bill of Rights, however, never wavered. He had seen the Mounted Police fire on the crowd near the Grain Exchange in 1919, and had seen the wounded workers brought to Weyburn from the 1931 police riot at Estevan. He had watched the brownshirts troop through the cobbled streets of the Reich. In a sense, Douglas was a man who heard voices. He kept an ear out, where no one else might notice, for rumours from the world of secret arrests and midnight trials. “We may wake up some day to realize that that’s not impossible on this North American continent,” he said in 1985,” where financial power is so highly concentrated in so few hands, with all the media for propaganda in the same hands and with the forces of democracy divided and scattered and diffused. It’s not impossible to imagine a fascist world.” [AB: The prophet hath spoken. Behold the present USA. For more details on what happened in not just the USA, but in the Western world, see Return of the Strong Gods.]“Douglas ended his speech with a throwback to the social gospel of his boyhood, a prayer from Woodsworth: “May we be the children of the brighter and better day which even now is beginning to dawn. May we not impede, but rather co-operate with the great spiritual forces which we believe are impelling the world onward and upward. For our supreme task is to make our dreams come true and to transform our city into the Holy City—to make this land in reality ‘God’s own country.’ ”

“Douglas took great satisfaction from the resurgence of social activism in the Christian churches. His roots remained firmly fixed in the social gospel. His conversation returned frequently to earlier days and the activities of the Fellowship for a Christian Social Order—a group that had provided early support in the development of his social philosophy” [AB: This came after his retirement from active politics.]“Honours and awards continued to arrive on Douglas’s desk from all points of the political compass. He had already been awarded honorary doctorates from many universities, from Vancouver to Halifax— something that had made him ponder the question of whether he was at last “becoming respectable.” [AB: It is remarkable that even after his long, distinguished career, he still pondered on whether he was “becoming respectable.”]

“He was a simple and humble person, with a great sensitivity to those around him. He brought to the political life of the country a civility that enriched the Canadian scene. He carried a remarkably light load of ideological dogma. His basic principles were as uncomplicated as he was, stemming from the social gospeller’s dedication to the ideas of the fatherhood of God and the brotherhood of man—ideas that provided both the goal of his political endeavours and the measure of his success. The ideals of his youth guided him consistently throughout his political career, being truly reflected in the last speech he made. For his principles he was prepared to stand alone, saying, like Martin Luther, “Here I stand, I cannot do otherwise.”Encountering Jesus in Revelation: The Apocalyptic Perspective That Calls Us to Follow the Lamb

Ben Boeckel (2024, 206 pp.)

Genre: Theological study

[Notes:

Ben Boeckel holds a PhD from Southern Methodist University, is pastor of the Grangeville Church of the Nazarene and has taught biblical studies and hermeneutics.

Sadly, the book suffers from frequent cases of poor editing. For example, “The tears form their eyes” instead of “The tears from their eyes.” Sentence structure sometimes requires reading three times to understand the meaning.

Nevertheless, Boeckel provides an accessible guide to the book of Revelation, showing how its apocalyptic vision calls Christians to follow Christ as the Lamb in every age, although not as deeply as several other books on the topic. To list just a few:

1. Surprised by Hope: Rethinking Heaven, the Resurrection, and the Mission of the Church, N.T. Wright, 2018

2. A New Heaven and a New Earth: Reclaiming Biblical Eschatology, J. Richard Middleton, 2014, 336

3. The Theology of the Book of Revelation, Richard Bauckham, 1993, 181

4. Revelation for the Rest of Us: A Prophetic Call to Follow Jesus as a Dissident Disciple, Scot McKnight, Cody Matchett, 2023, 336

5. Reading Revelation Responsibly: Uncivil Worship and Witness: Following the Lamb into the New Creation, Michael Gorman, 2011, 230

6. Reversed Thunder: The Revelation of John and the Praying Imagination, Eugene Pederson, 1991, 224

7. Discipleship On The Edge: An Expository Journey Through the Book of Revelation, Darrel Johnson, 2021, 436

]

Curated Quotes:

“It is worth reiterating that biblical prophecy is not first and foremost about predicting the future. When Rev 10–11 fixates on the church’s prophetic ministry, it is not a summons for Christians to begin prognosticating regarding stock market crashes, one world governments, etc. Rather, it is a reminder that our role is to proclaim God’s message—the gospel—to a world in need of salvation.”

“Revelation also draws on the larger story of Israel—especially the exodus—as it beckons the church to follow the Lamb. As prophecy, the point of John’s imagery and symbolism is to comfort those afflicted in the church and to afflict those who are too comfortable.”“[In John’s vision in Revelation,] Babylon’s merchants comprised a second group of mourners. Their dirge followed a long catalogue of the various luxuries trafficked in the Roman Empire. It is a list of merchandise for which the empire’s upper classes paid handsomely. With virtually no middle class in society, money became no object for those with wealth. As such, they could spend more than the annual income of a day-laborer on precious cargoes without thinking about it. In this economy, the merchants enriched themselves by leveraging society’s economic inequality.” [AB: Revelation casts a shadow on the economic realities of our present day.]

A Truce That Is Not Peace

Miriam Toews (2025, 192 pp.)

Genre: Memoir

[Notes:

Miriam Toews published this book at the age of 61. She was raised in Winnipeg and now resides in Toronto. She is best known for her novel, Women Talking, written in 2018 and adapted into an Oscar-winning movie in 2023.

Although Toews is known for her novels, in this recent book she turns inward in an unconventional memoir, which in some ways is like looking at the raw material for her novels and experimenting with how to “rearrange her words”. Her look back at her life shows her struggling with the suicides of her father and sister, with mental health issues, memories of travel in Europe, and a recurring fixation with creating a “Wind Museum”! Her stream-of-consciousness writing style captures the texture of a life lived close to both pain and wonder. It contributes to the description of the apparent brokenness of her childhood and early adulthood in the context of her Mennonite background, but she does have the ability to find moments of brightness and humanity in even the darkest narratives.

The book comes with a language warning!]

Curated Quotes:

“And yet I’ve come to believe, and in rare moments can almost feel, that like an illness some vestige of which the body keeps to protect itself, pain may be its own reprieve; that the violence that is latent within us may be, if never altogether dispelled or tamed, at least acknowledged, defined, and perhaps by dint of the love we feel for our lives, for the people in them and for our work, rendered into an energy that need not be inflicted on others or ourselves, an energy we may even be able to use; and that for those of us who have gone to war with our own minds there is yet hope for what Freud called ‘normal unhappiness,’ wherein we might remember the dead without being haunted by them, give to our lives a coherence that is not ‘closure,’ and learn to live with our memories, our families, and ourselves amid a truce that is not peace.” —Christian Wiman [AB: Toews occasionally inserts excerpts from books by Christian Wiman. This quote comes from Ambition and Survival: Becoming a Poet.]

“A few weeks later, I was walking along the river again. I had begun to walk at night, after I’d helped bathe the kids and put them to bed and after my mother and I had returned to our apartment and she had gone to bed, in the living room, all tucked in and ready to begin her nighttime shouting. I was trying to organize my thoughts, and everything, every thought, every memory, embarrassed me. I had never experienced such a deep, excruciating sense of embarrassment, of mortification. Was it the embarrassment of wanting to write when I was, by now, a woman in my fifties, a grandmother of four, responsible for the care of her own old mother? I needed my body to turn itself inside out, to expose what was inside and let it blow away and become mist or dust or whatever happens to what’s inside a person when her body is turned inside out. I wanted so badly to stop obsessing about rearranging words. I wanted to disappear, or at least I wanted my mind to disappear, to step aside, to stop. I wanted to exist fully as … I didn’t know what. As a grandmother, perhaps. As a benign but wise grandmother, with a soft lap, a smile, no thoughts but ones of love, encouragement, optimism. No need to rearrange words. And as a better daughter to my old, dying mother, patient, confiding, tender. I felt guilty about everything. I really believed that I had been a terrible mother to my kids, never fully present, as they say, and that the reason for that was that I was always, always a million miles away in my head, rearranging words, long dark sentences on white pages, like the dark, crumbling bridges seen against this snowy city from airplane windows. Maybe I had a soft lap, and a smile on my face, but the truth was I was the opposite of everything I wanted to be. I was so ashamed of being a woman in her fifties who was not the woman she wanted to be. Wasn’t that the domain of adolescence? I tried to empty my mind of words. In bed at night, I imagined that my skull was a smooth white shell, empty and glistening. I burned soy-wax candles with soothing scents of grasslands and rain on city pavement. I repeated mantras to myself: relinquish control, relinquish words, relinquish language, there is no such thing as letters, there are no words left in the universe, nothing left to rearrange. I walked and walked, quickly so I wouldn’t freeze, and imagined that I was walking away from words, that the words were frozen under the thick ice, that I was stamping them out with my feet as I walked, one after another, creating a vast, icy distance between them and me.” [AB: Her obsession with rearranging words seems like a metaphor for her desire to rearrange her life experience into some more aligned with her desires, and yet having to let that go.]Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future

Dan Wang (2025, 288 pp.)

Genre: Geopolitics / Technology

[Notes:

Dan Wang is a research fellow at Stanford’s Hoover Institution and previously technology analyst for Gavekal Dragonomics in China. The book was published in August.

Wang moved to Canada at the age of seven with his parents and grew up in Ottawa. From there his family moved to Pennsylvania where his parents still reside. As someone who has split much of their life between North America and China, he presents an unbiased view of the strengths and weaknesses of both nations, unhesitant to outline the failings of the Chinese state government. Although the book seems balanced, it may come across as too simplistic in its interpretation of the challenges each nation faces.

Comparing USA and China, USA is identified as the land of lawyers (regulation, prevent growth); China is the land of engineers who build, build, build. USA is the land of consumption; China is the land of production. USA provides social safety nets and services; China limits social supports, thereby forcing people to save for contingencies themselves. China builds complete cities of 350,000 residents at one time for the purpose of production, complete with all services needed to support that production. China is an autocratic government, and if as a builder you fail to use your capital well, the government can force you into jail or death.

The chapters dedicated to China’s “one-child” policy and “zero-Covid” policy felt disproportionately weighted given their overall contribution to the book’s central thesis. While these chapters offered valuable historical context and insight into the government’s “social engineering” bias, the space might have been better used for a more in-depth analysis and greater emphasis on military comparisons and projections.]

Curated Quotes:

“Through the 1990s and especially after 2001 (when China acceded to the World Trade Organization), American companies were busy moving manufacturing work to China. Apple’s collaboration in Shenzhen helped transform the city into the world’s most innovative hub for electronics production. But this win for Apple’s shareholders has been a loss for American power.

US manufacturing employment peaked in 1980 at nineteen million workers. In 2000, it still had seventeen million. Then it collapsed over the next decade, in part due to China, in part due to technology changes, and especially after the global financial crisis, when the workforce fell to just eleven million in 2010. In 2025, the United States has around thirteen million manufacturing workers.”

“The problem lies with American policymakers and executives who fail to grasp the importance of process knowledge.

American manufacturers spent the better part of three decades unwinding its stock of process knowledge when it opened so many factories in China. Every US factory closure represents a likely permanent loss of production skill and knowledge. Line workers, machinists, and product designers are thrown out of work; then their suppliers and technical advisers struggle as well. Entire American communities of engineering practice have dissolved, leaving behind a region known as the Rust Belt. Some mayors and governors tried to stem this receding tide. But they were continuously scorned by economists and executives, who sought low-wage production in the name of globalization.”“As iPhone sales started to explode, Foxconn [the project management company] faced a constant hunger for workers. Soon enough, it had outgrown Shenzhen. Rather than wait for migrant workers to move to Shenzhen, Gou decided to move Foxconn to the biggest suppliers of workers. Factories sprang up in China’s most populous regions: Sichuan and Chongqing in the southwest, the eastern provinces around Shanghai, and the northern province of Henan. These regions remain major production sites for Apple, the biggest of which is in Henan’s capital city of Zhengzhou. At peak season, Zhengzhou has the capacity to employ around 350,000 people.”

“The iPhone has become one of the rarest sorts of consumer products—both ubiquitous and coveted as a status object. It is also the crowning success of the trade relationship between two countries, in which American inspiration and marketing savvy met China’s millions of workers, managed by contract manufacturers like Taiwan’s Foxconn, to make state-of-the-art electronics. It wasn’t easy to organize a workforce to assemble thousands of components into the most complex consumer product the world has ever known. Mastering this feat propelled Apple to become the first trillion-dollar company.” [AB: We assume that China and Taiwan are at loggerheads and on the verge of war, but here we have an example of a large and critical company from Taiwan, Foxconn, providing valuable support for China’s production industry inside China itself.]“The results of the Chinese government’s unceasing interventions in the economy are at best ambiguous. Economic studies have shown that the recipients of Chinese subsidies have, on average, lower productivity growth. Xi’s aggressive promotion of industry has triggered trade wars with not just the United States but also many developing countries as well. China’s tech successes are no convincing demonstration that a wise state can plan the future.”

“China took up a lot of the dirty industries that the United States was happy to get rid of. In some cases, literally: Rare earth metals are not really rare. Processing them, however, demands enormous amounts of energy and water while spewing carcinogens into the atmosphere. Few parts of the Western world have the stomach for processing rare earth metals, which is why China controls this supply chain.”“China would be better off if engineers confined themselves to building in the physical world. But they have been more ambitious than that. Beijing is made up, unfortunately and fundamentally, of social engineers. One of the major threats to China’s tech power—and its global position more broadly—is the result of a disastrous decision undertaken decades ago to engage in population engineering.” [AB: Referring to the “one-child” policy.]

“Song’s example [of providing the impetus for following the “one-child” policy] is one reason that I’ve become suspicious of anyone who advocates “following the science.” We have to get quite worried if anyone in power starts saying that science alone is an object to be pursued rather than having to situate it in a social and ethical context. There is still truth, I think, to Winston Churchill’s quip that scientists should be “on tap, not on top.”“Far from celebrating this decline [of a population decline to 700,000 by 2100], Xi Jinping and the rest of China’s leadership are trying to reverse it. Each year after 2022 will see slightly fewer people powering the Communist Party’s great odyssey toward national rejuvenation. Maternity wards are starting to shut down in several provinces since there are fewer newborns. In 2025, adult diapers are expected to outsell baby diapers.”

“I found one item particularly quite irksome on my return to America in 2023: a yard sign that begins “In this home we believe science is real.” The Communist Party “followed the science” of zero-Covid to its logical conclusion: barring people from their homes, testing people on a near-daily basis, and doing everything else it could to break the chains of transmission. Four decades ago, it “followed the science” to forcibly prevent many pregnancies in the pursuit of the one-child policy.

We can agree that “science is real.” But we have to keep in mind that there is a political determination involved with how to interpret the science.”“The United States has been weakened not only by a procedure-obsessed left—which has become so determined to avoid the errors of [Robert] Moses [a “bull in the china shop” New York builder in the early 20th century] that few big works are built at all—but also a thoughtlessly destructive right. I bring up Moses to suggest that the American left needs to rouse itself to deal with the problems of the present day rather than the problems of the previous midcentury.

The American right, I hope, can remember that it is possible to build wonders using the government. In 2025, the tech right celebrates the achievements of Elon Musk, whose Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) seeks to shred the federal government. No one can dispute that the US government is capable of astonishing inefficiency, but it used to be able to deliver the technologically astonishing too.”

“The United States will be stronger if it can manufacture. If it does not recover manufacturing capacity, the country will continue to be forcibly deindustrialized by China. US global power will be reduced if people around the world find it more attractive to drive Chinese cars, deploy Chinese robots, and fly Chinese planes. The world is more dangerous if Beijing believes that the United States has insufficient ships and munitions to respond to an aggressive act against Taiwan or in the South China Sea. If the two superpowers fight in East Asia, it’s not at all clear that the United States will win. America has to build to stave off being overrun commercially or militarily by China.

The United States will be stronger if it builds more homes. American progressives have a slogan that every billionaire is a policy failure. Since common folks are more on my mind, I propose an amendment: Every rise in housing prices is a policy failure. Prosperous places with substantial job creation—especially New York, San Francisco, and Boston—have perversely done the most to block new housing.”“The engineering state has delivered great things. But the Communist Party is made up of too many leaders who distrust their own people and have little idea how to appeal to the rest of the world. They will continue to bring literal-minded solutions for their problems, attempting to engineer away their challenges, leaving the situation worse than they found it. Beijing will never be able to draw on the best feature of the United States: Embracing pluralism and individual rights. The Communist Party is too afraid of the Chinese people to give them real agency. Beijing will not recognize that the creatives and entrepreneurs it is chasing into exile are not the enemy. It will not accept that their creative energy could bring as much prestige to China as great public works.”

“The United States has lost its ability not only to build but also, in part, to govern. The procedure-obsessed left and the destructive right have robbed from the people the sense that physical dynamism is desirable. But the United States has pluralistic values, which positions it to better figure out the right solutions.”“What the United States presently lacks is the urgency to make the hard choices to build. Americans have to trust that society can flourish without empowering lawyers to micromanage everything. The United States should embrace its transformational urge. I hope one day that America can declare itself to be a developing country too [AB: As opposed to a “developed” country.] It can demonstrate that the country is able to reform itself, get unstuck from the status quo, and ultimately unlock as much as possible of human potential. “Developing” is a term to embrace with pride.” [AB: Good luck. This is not going to happen until there is a huge and overwhelming social and cultural and spiritual change. Culture leads politics.]

Reading scrapes the moss from our thinking! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my efforts.

Recommend a book…

Thank-you for reading [Notes] and “Quotes”!

November’s [Notes] and “Quotes” will include the following books, along with others:

Nobody’s Girl: A Memoir of Surviving Abuse and Fighting for Justice, Virgina Roberts Giuffre (2025, 400 pp.)

Time to Think: Listening to Ignite the Human Mind, Nancy Kline (2021, 256 pp.)

America’s Best Idea: The Separation of Church and State, Josh Dawsey (2025, 160 pp.)

From Extraterrestrials to Animal Minds: Six Myths of Evolution, Simon Conway Morris (2022, 272 pp.)

![[Notes] and "Quotes" by Arnie Berg](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!pJ9d!,w_40,h_40,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fbb88adc7-d439-40a5-9080-eeed420c842d_1280x1280.png)

![[Notes] and "Quotes" by Arnie Berg](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!4edT!,e_trim:10:white/e_trim:10:transparent/h_72,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F3c6bff99-5c60-4ffb-b72f-0a45a0e12514_1100x220.png)

![[Notes] and "Quotes"'s avatar](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!lQGu!,w_36,h_36,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F37660695-8e60-4950-ac5f-4ec4f45b0cf4_1793x1793.jpeg)