Illuminating Insight: Waiting for the End of the World: The Story Behind Rapture Culture

The world didn’t end, but several generations learned that it could in a certain way, and it shaped the way they lived.

“My hope is built on nothing less

Than Scofield’s notes and Moody Press;

I dare not trust this Thompson’s chain,

But wholly lean on Scofield’s fame.”

This old parody makes me smile. For a generation of evangelicals, the Scofield Reference Bible and Moody Press were anchors of certainty that mapped the sweep of world history according to divine dispensations and biblical prophecy. They offered a coherent, charted order to a chaotic world.

Behind this humorous critique of dispensationalist fundamentalism lies a serious question:

How did one interpretive system come to shape the imagination of North American evangelicals for much of the twentieth century, and what kind of cultural worldview did it produce?

And how did that mindset impact the culture of the broader social context?

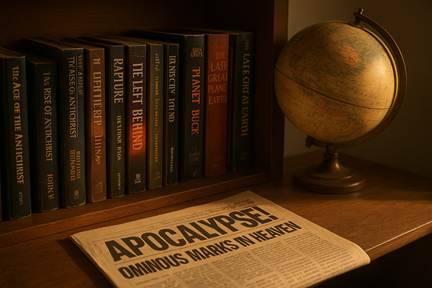

Selling the End: Rapture and Consumer Culture

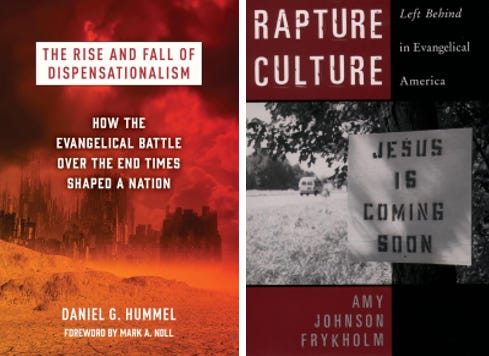

In my recent Book Portrait, I featured an illustrated summary of Daniel Hummel’s recent book, The Rise and Fall of Dispensationalism: How the Evangelical Battle Over the End Times Shaped a Nation. Hummel traces how this theological movement, which began as an attempt to harmonize Scripture, eventually intersected with North American culture and political expression.

But theology is never just abstract. It takes hold of our imagination and gets lived out. And that is where Amy Johnson Frykholm’s Rapture Culture: Left Behind in Evangelical America picks up the story, not among scholars, but among the readers who lived by the hope of Christ’s imminent return.

Today’s Illuminating Insight takes a closer look at how advocates of the dispensational movement defined themselves and how this played out in the general culture. Each generation translates its hope of Christ’s return into its own moment in time. The once-confident charts of 20th century dispensationalism have given way to a more conventional vision of renewal, but dispensationalism still retains a residual influence in more conservative Christian circles. This expression of evangelicalism is referred to as Rapture Culture and this Illuminating Insight is a journey into that world that helps us understand how dispensational eschatology shaped the lives, fears, and hopes of millions.

Stories of the End

Where Hummel’s book focuses on theologians, Frykholm’s book focuses on readers. She interviews ordinary Christians who devoured Late Great Planet Earth and the Left Behind series of novels, tracing how global events and politics intersected with faith through the lens of impending apocalypse, who scanned headlines for clues that history was winding down.

In these believers’ minds, faith and current events merged into a single, coherent narrative, where believers live grounded on earth but looking for heaven, scanning headlines for confirmations for their beliefs. The formation of Israel in 1948, wars in the Middle East, or the European Union all seemed like signs confirming prophecy.

This system of beliefs is not just a theology; it’s a narrative ecosystem. It’s a stirring drama complete with villains and heroes, crisis and rescue, tribulation and triumph, a sense that present chaos has meaning, suffering has purpose, and a certainty that all will be well in the end.

As the Apostle Peter wrote,

“We have the prophetic word made surer, to which you do well to pay attention as to a lamp shining in a dark place” (2 Peter 1:19).

For the Rapture culture, that lamp illuminated every event as if it were a step toward the final act.

From Doctrine to Drama

As Hummel shows, the dispensational system that emerged in the 19th century as a careful theological framework became something larger in the 20th century, a drama of divine order amid moral decay. That story moved out of the seminaries and into the evangelical culture in the 1990s when Tim LaHaye and Jerry Jenkins released their Left Behind series.

This framework became a pop-eschatology as it captured the imagination of ordinary believers with mass-market storytelling.

The novels (and movies) succeeded not only because readers believed the prophecies, but because they provided a moral framework. In a time of confusion, they offered clarity and a vision of right living, and final hope. Overcoming the trials of today promised an escape from the chaos to come. Left Behind became the evangelical equivalent of a national foundational myth, a framework of identity, belonging, and destiny,

The word “apocalypse” itself was transformed. Once it meant an unveiling, a moment when hidden truth breaks into view. Now it evokes images of global ruin and chaos. Revelation became destruction; disclosure became disaster.

Marketing the End-Times

Rapture belief, Frykholm notes, often merges biblical literalism with consumer culture. Prophecy conferences, novels, movies, and timelines all feed an attitude of expectation and anticipation. Bumper stickers foreshadow self-driving cars (“In case of rapture, this car will be unmanned”). Frykholm calls the result an “imaginative geography” of salvation.

In this geography, America is cast as both Babylon and a chosen nation. Israel is a prophetic centerpiece. Global politics is the stage upon which God’s drama unfolds. The latest evening news is factored into the rapture interpretive framework, Revelation in real time.

The frantic drama creates a sense of fear and anxiety, but behind the anxiety lies the deeply human desire for meaning, for the assurance that the story is going somewhere and that the divine Author has not lost control. This mixture of anxiety and assurance gave believers both fear and meaning, a sense that the Author of history still held the pen. Yet, as Paul warned the Thessalonians,

“Do not be quickly shaken in mind or alarmed… as though the day of the Lord has already come” (2 Thessalonians 2:2).

The Rapture culture lived in tension with that admonition, vacillating between vigilance and panic.

Frykholm’s interviews reveal that for many believers, church life became a surrogate family. The spiritual kinship often felt purer, safer, and more enduring than their own homes. This sense of belonging, though sometimes shallow, anchored their faith within a drama larger than their daily dysfunction. Rapture Culture, at its heart, was about finding a home in the story of the end.

Still Left Behind

Two decades later, the Left Behind era has largely passed, but its instincts persist. The sense of being a faithful remnant in a hostile culture, the fascination with crisis and chaos, and the habit of reading history through apocalypse have morphed into new forms. They now appear in political rhetoric, culture wars, and new media formats.

In that sense, Rapture Culture feels prophetic itself. It reminds us that the “end of the world” is never merely about the end. It’s about how we live now and think about our place in the unfolding history of the world. Jesus’ call was not to escape but to endure: “Occupy till I come” (Luke 19:13, KJV)

A Final Reflection

Frykholm’s work shows that beneath the charts and headlines is a longing for transcendence, for a story big enough to channel both fear and hope. It provides a lesson that humanizes rapture culture rather than dismissing it. Our own generation can learn to recover an eschatology that doesn’t end in escape, but in renewal, one that looks for healing and building for the Kingdom, not for the world’s destruction.

Scripture’s final vision is not of escape but restoration:

“Then I saw a new heaven and a new earth… and the holy city, new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God” (Revelation 21:1–2).

To recover that vision is to rediscover hope not as flight, but as faithfulness, to live as builders for the Kingdom in the tension between the “already” and the “not yet.”

Why It Matters

Did you grow up with Left Behind or prophecy charts on your church wall?

How did that shape your sense of time, faith, or fear?

How have you reimagined “the end”, and what does “hope” mean to you now?

Next Month’s Book Portrait

Next month’s Book Portrait looks at how contemporary theologians are reimagining eschatology, not as countdown, but as covenant; not from fear to flight, but from faith to renewal.

October’s [Notes] and “Quotes” will include the following books, along with others:

Tommy Douglas: The Road to Jerusalem, Thomas McLeod, Ian McLeod (1987, 341 pp.)

The Origins of Totalitarianism, Hannah Arendt (1951, 576 pp.)

A Truce That Is Not Peace, Miriam Toews (2025, 192 pp.)

107 Days, Kamela Harris (2025, 320 pp.)

Return of the Strong Gods: Nationalism, Populism, and the Future of the West, R. R. Reno (2021, 208 pp.)

Encountering Jesus in Revelation: The Apocalyptic Perspective That Calls Us to Follow the Lamb, Ben Boeckel (2024, 206 pp.)

Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future, Dan Wang (2025, 288 pp.)

Thank you for reading October’s Illuminating Insight!

![[Notes] and "Quotes" by Arnie Berg](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!pJ9d!,w_40,h_40,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fbb88adc7-d439-40a5-9080-eeed420c842d_1280x1280.png)

![[Notes] and "Quotes" by Arnie Berg](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!4edT!,e_trim:10:white/e_trim:10:transparent/h_72,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F3c6bff99-5c60-4ffb-b72f-0a45a0e12514_1100x220.png)